I Bought A Little Story aka Shuffle Synchronicities: Volume 2 - #387

"Sad Times" by MNYS - 01/10/23

“Sad Times” by MNYS

Back in late November, there was a mention in post 385 of a piece submitted to The New Yorker & how if it wasn’t accepted for publication it would be self-published here

As well been rewriting an example of something we’re calling Remix Lit, in this case, Donald Barthelme’s story “I Bought a Little City” sampled into “I Bought a Little Story”, in light of recent Elon Musk developments, which was submitted to The New Yorker on Wednesday. If 🎩 doesn’t accept it, which is quite likely LOL, it’ll be self-published here 🧑🔧!

That day has come

No, it’s not in The New Yorker

LOL

And while there is not going to be someone here saying they made an old-guard mistake by choosing a Paul Rudnick Shouts to cover Musk & Twitter instead

There’s also not going to be someone here saying ‘my’ story isn’t better

It just might be that ‘my’ writing doesn’t belong in The New Yorker anymore

Or as this song “Sad Times” by MNYS sings:

I can't with you, I wanna say

Or they can’t with me, they’re saying

Both/and

LOL

And I know it hurts sometimes but I've

Unplugged from my past life and I

Feel like I'm taking too much space

It hurts sometimes not to write in the more conventional ways of humor

To have unplugged from that past life

And to realize this piece probably took up too much space

Not just in the literal word count

It took up too much space with my ‘self’

And that's a lot for one reply

But I'll ‘like' your picture just in case

I will always still like the magazine

Love it

And hope to one day return to its pages

But also feel like:

I guess that I'm really proud of you

I loved you so much that I left

9-5, doing what you need to do

I've told you there was always more to you

I can't with you, I wanna say

I am really proud of what was written

(Readers of Volume 1 might recall there was an earlier draft of this story published on the Substack in post 89 but it wasn’t submitted yet)

Even if the result continues to suggest a leaving of traditional commercial platforms of publication

Of perhaps continuing to need to work 9-5

Doing what is needed to be done

In order to provide time

To create what shows there is always more

To me

And to art

& the spirit

It’s funny that the song I feel might best capture this moment as a memoiristic synchronicity is something that’s not on Spotify yet LOL

“Hollywood Baby” by 100 gecs with it’s chorus “You’ll Never Make It In Hollywood, Baby!

But without further adieu…

I can't with you, New Yorker

But I can,

And I wanna,

With all of you!

I Bought a Little Story

by

David Cowen

So I bought a little story (it was I Bought a Little City by Donald Barthelme). And here it is:

I Bought a Little City by Donald Barthelme

So I bought a little city (it was Galveston, Texas) and told everybody that nobody had to move, we were going to do it just gradually, very relaxed, no big changes overnight. They were pleased and suspicious. I walked down to the harbor where there were cotton warehouses and fish markets and all sorts of installations having to do with the spread of petroleum throughout the Free World, and I thought, A few apple trees here might be nice. Then I walked out this broad boulevard which has all these tall thick palm trees maybe 40 feet high in the center and oleanders on both sides, it runs for blocks and blocks and ends up opening up to the broad Gulf of Mexico — stately homes on both sides and a big Catholic church that looks more like a mosque and the Bishop’s Palace and a handsome red brick affair where the Shriners meet. I thought, What a nice little city, it suits me fine.

It suited me fine so I started to change it. But softly, softly. I asked some folks to move out of a whole city block on I Street, and then I tore down their houses. I put the people into the Galvez Hotel, which is the nicest hotel in town, right on the seawall, and I made sure that every room had a beautiful view. Those people had wanted to stay at the Galvez Hotel all their lives and never had a chance before because they didn’t have the money. They were delighted. I tore down their houses and made that empty block a park. We planted it all to hell and put some nice green iron benches in it and a little fountain — all standard stuff, we didn’t try to be imaginative.

I was pleased. All the people who lived in the four blocks surrounding the empty block had something they hadn’t had before, a park. They could sit in it, and like that. I went and watched them sitting in it. There was already a black man there playing bongo drums. I hate bongo drums. I started to tell him to stop playing those goddamn bongo drums but then I said to myself, No, that’s not right. You got to let him play his goddamn bongo drums if he feels like it, it’s part of the misery of democracy, to which I subscribe. Then I started thinking about new housing for the people I had displaced, they couldn’t stay in that fancy hotel forever.

But I didn’t have any ideas about new housing, except that it shouldn’t be too imaginative. So I got to talking to one of these people, one of the ones we had moved out, guy by the name of Bill Caulfield who worked in a wholesale tobacco place down on Mechanic Street.

“So what kind of a place would you like to live in?” I asked him.

“Well,” he said, “not too big.”

“Uh-huh.”

“Maybe with a veranda around three sides,” he said, “so we could sit on it and look out. A screened porch, maybe.”

“Whatcha going to look out at?”

“Maybe some trees and, you know, the lawn.”

“So you want some ground around the house.”

“That would be nice, yeah.”

“’Bout how much ground are you thinking of?”

“Well, not too much.”

"You see, the problem is, there's only x amount of ground and everybody's going to want to have it to look at and at the same time they don't want to be staring at the neighbors. Private looking, that's the thing."

“'Well, yes,” he said, “I’d like it to be kind of private.”

“Well,” I said, “get a pencil and let’s see what we can work out.”

We started with what there was going to be to look at, which was damned difficult. Because when you look you don't want to be able to look at just one thing, you want to be able to shift your gaze. You need to be able to look at at least three things, maybe four. Bill Caulfield solved the problem. He showed me a box. I opened it up and inside was a jigsaw puzzle with a picture of the Mona Lisa on it.

“Lookee here,” he said. “If each piece of ground was like a piece of this-here puzzle, and the tree line on each piece of property followed the outline of a piece of the puzzle — well, there you have it, Q.E.D. and that’s all she wrote.”

“Fine,” I said. “Where are the folk going to park their cars?”

“In the vast underground parking facility,” he said.

“O.K., but how does each householder gain access to his household?”

“The tree lines are double and shade beautifully paved walkways possibly bordered with begonias,” he said.

“A lurkway for potential muggists and rapers,” I pointed out.

“There won’t be any such,” Caulfield said, “because you’ve bought our whole city and won’t allow that class of person to hang out here no more.”

That was right. I had bought the whole city and could probably do that. I had forgotten.

“Well,” I said finally, “let’s give ’er a try. The only thing I don’t like about it is that it seems a little imaginative.”

We did and it didn’t work out badly. There was only one complaint. A man named A.G. Bartie came to see me.

“Listen,” he said, his eyes either gleaming or burning, I couldn’t tell which, it was a cloudy day, “I feel like I’m living in this gigantic jiveass jigsaw puzzle.”

He was right. Seen from the air, he was living in the middle of a titanic reproduction of the Mona Lisa, too, but I thought it best not to mention that. We allowed him to square off his property into a standard 60 x 100 foot lot and later some other people did that too — some people just like rectangles, I guess. I must say it improved the concept. You run across an occasional rectangle in Shady Oaks (we didn't want to call the development anything too imaginative) and it surprises you. That's nice.

I said to myself:

Got a little city

Ain’t it pretty

By now I had exercised my proprietorship so lightly and if I do say so myself tactfully that I wondered if I was enjoying myself enough (and I had paid a heavy penny too — near to half my fortune). So I went out on the streets then and shot six thousand dogs. This gave me great satisfaction and you have no idea how wonderfully it improved the city for the better. This left us with a dog population of 165,000, as opposed to a human population of something like 89,000. Then I went down to the Galveston News, the morning paper, and wrote an editorial denouncing myself as the vilest creature the good God had ever placed upon the earth, and were we, the citizens of this fine community, who were after all free Americans of whatever race or creed, going to sit still while one man, one man, if indeed so vile a critter could be so called, etc. etc.? I gave it to the city desk and told them I wanted it on the front page in fourteen-point type, boxed. I did this just in case they might have hesitated to do it themselves, and because I'd seen that Orson Welles picture where the guy writes a nasty notice about his own wife's terrible singing, which I always thought was pretty decent of him, from some points of view.

A man whose dog I’d shot came to see me.

“You shot Butch,” he said.

“Butch? Which one was Butch?”

“One brown ear and one white ear,” he said. “Very friendly.”

“Mister,” I said, “I’ve just shot six thousand dogs, and you expect me to remember Butch?”

“Butch was all Nancy and me had,” he said, “we never had no children.”

“Well, I’m sorry about that,” I said, “but I own this city.”

“I know that,” he said.

“I am the sole owner and I make all the rules.”

“They told me,” he said.

“I’m sorry about Butch but he got in the way of the big campaign. You ought to have had him on a leash.”

“I don’t deny it,” he said.

“You ought to have had him inside the house.”

“He was just a poor animal that had to go out sometimes.”

“And mess up the streets something awful?”

“Well,” he said, “it’s a problem. I just wanted to tell you how I feel.”

“You didn’t tell me,” I said. “How do you feel?”

“I feel like bustin’ your head,” he said, and showed me a short length of pipe he had brought along for the purpose.

“But of course if you do that you’re going to get your ass in a lot of trouble,” I said.

“I realize that.”

“It would make you feel better, but then I own the jail and the judge and the po-lice and the local chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union. All mine. I could hit you with a writ of mandamus.”

“You wouldn’t do that.”

“I’ve been known to do worse.”

“You’re a black-hearted man,” he said. “I guess that’s it. You’ll roast in Hell in the eternal flames and there will be no mercy or cooling drafts from any quarter.”

He went away happy with this explanation. I was happy to be a black-hearted man in his mind if that would satisfy the issue between us because that was a bad-looking piece of pipe he had there and I was still six thousand dogs ahead of the game, in a sense. So I owned this little city which was very, very pretty and I couldn’t think of any more new innovations just then or none that wouldn’t get me punctuated like the late Huey P. Long, former governor of Louisiana. The thing is, I had fallen in love with Sam Hong’s wife. I had wandered into this store on Tremont Street where they sold Oriental novelties, paper lanterns and cheap china and bamboo birdcages and wicker footstools and all that kind of thing. She was smaller than I was and I thought I had never seen that much goodness in a woman’s face before. It was hard to credit. It was the best face I’d ever seen.

“I can’t do that,” she said, “because I am married to Sam.”

“Sam?”

She pointed over to the cash register where there was a Chinese man, young and intelligent-looking and pouring that intelligent look at me with considered unfriendliness.

“Well, that’s dismal news,” I said. “Tell me, do you love me?”

“A little bit,” she said, “but Sam is wise and kind and we have one and one-third lovely children.”

She didn’t look pregnant but I congratulated her anyhow, and then went out on the street and found a cop and sent him down to H Street to get me a bucket of Colonel Sanders’ Kentucky Fried Chicken, extra crispy. I did that just out of meanness. He was humiliated but he had no choice. I thought:

I own a little city

Awful pretty

Can’t help people

Can hurt them though

Shoot their dogs

Mess ’em up

Be imaginative

Plant trees

Best to leave ’em alone?

Who decides?

Sam’s wife is Sam’s wife and coveting

Is not nice.

So I ate the Colonel Sanders’ Kentucky Fried Chicken extra crispy, and sold Galveston, Texas, back to the interests. I took a bath on that deal, there’s no denying it but I learned something — don’t play God. A lot of other people already knew that, but I have never doubted for a minute that a lot of other people are smarter than me, and figure things out quicker, and have grace and statistical norms on their side. Probably I went wrong by being too imaginative, although really I was guarding against that. I did very little, I was fairly restrained. God does a lot worse things, every day, in one little family, any family, than I did in that whole little city. But He’s got a better imagination than I do. For instance, I still covet Sam Hong’s wife. That’s torment. Still covet Sam Hong’s wife, and probably always will. It’s like having a tooth pulled. For a year. The same tooth. That’s a sample of His imagination. It’s powerful.

So what happened? What happened was that I took the other half of my fortune and went to Galena Park, Texas, and lived inconspicuously there, and when they asked me to run for the school board I said No, I don’t have any children.

Thank you. For reading the original. Except I didn’t buy the story. Because it was already sold to The New Yorker in 1974. But you also can’t buy a little city, except in fiction, unless you’re Kim Basinger, who tried to in real life in the 90s. It seems Elon Musk has been trying to, too, recently, before, you know, everything went, atwitter.

The author, Donald Barthelme, is dead, like most pun humor, and perhaps my relationship with The New Yorker, after publishing one inspired piece of juvenalia for their Shouts & Murmurs section about Kanye West saying he doesn’t read books while promoting one in 2009 under the name Dave Cowen, written perhaps during one of my own episodes of hypomania.

I’m trying out my birth name, David, instead now, kinda the opposite of what Ye is doing now (even though, to be honest, I didn’t read books myself for a period after publishing that) as I consider submitting this remix in the year 2022, and I’m pretty sure I’m not having any episodes of mania, hypo or not.

If I did submit it, and The New Yorker is reading this, they are probably perplexed, likely suspicious, not to mention their readers.

I say, Relax, we’re going to do things gradually, no big changes overnight, and, most importantly, Everyone can have their own say here.

Maybe, just maybe, you’re also a little pleased so far.

I read through the rest of Barthelme’s original first paragraph about the spread of petroleum throughout the Free World, fish markets, a big Catholic church that looks more like a mosque, and some apple trees, etc., and I thought:

A few emojis here might be nice.

🛢🌐🎣⛪️🕌🍎🌲

What a nice little story, it suits me fine.

It suited me so fine I wrote that I started to not want to change it.

Even though I still did want to. And LOUDLY, LOUDLY!

For instance, the next part where Barthelme has his narrator (What should I call him? I wondered. I can’t just call him the narrator. That’s boring. And it’s my story now! Oh, right!) where Barthelme has Elon Musk ask some folks to move out of a whole city block on I Street, so Musk can tear down their houses.

I change it so that Musk puts the people, not into the Galvez Hotel, which is the nicest in town, with its sea view, but instead, his colony on Mars, which is the first and only, so the nicest there.

Well, that’s how I had it in the first draft. The bit continued with a joke about how “Does anyone even want to live in a colony on Mars? If the people on I Street lived in a colony on Mars, how would they see the rest of the people in their little city? Zoom? No one’s delighted with that?”

Nor was I now. And rewriting it, I doubt Musk will have enough money after buying Twitter, this little city, and this little story, to also build a colony on Mars (though the internal logic of who purchased the story is now unclear to me as well as many aspects of its tenses of grammar).

I guess I should listen to Barthelme and not try to be imaginative.

I’ll stick with the standard stuff.

Musk puts them into the Galvez and plants the empty I Street block all to hell to make it into a park.

Except now I’m not pleased. I like to be imaginative.

That’s why I like Donald Bartheleme.

And The New Yorker.

I imagine you readers feel the same?

Maybe the story needs a little GIF?

Oops was that GIF too imaginative?

I went with a reference to the next part of the story where Barthelme has his narrator go watch the people in his little city sit in their new park but says, “There was already a black man there playing bongo drums. I hate bongo drums. I started to tell him to stop playing those goddamn bongo drums but then I said to myself, No, that’s not right. You got to let him play his goddamn bongo drums if he feels like it, it’s part of the misery of Democracy, to which I subscribe.”

Along with satirizing plutocrat tyranny, to which I subscribe, it seems like Barthelme is also satirizing impulses of boorish racism.

But by doing the latter in this way, was he merely buttressing them?

But did I merely do the same thing by speculating about Barthelme’s own latent impulses?

Instead of just excising that content from the story I am ostensibly now the steward of and that others probably won’t go back to read the original of (even if it is now fully quoted above)?

Maybe sometimes imagination is regression in disguise?

I dunno.

I could ask Bartheleme, if only his dead body were also animate?

Like I wish sometimes for my Dead Father.

Also, does adding a GIF mean this can only be a digital Daily Shouts?

Are they less money still?

I decide to go all in on a digital Daily Shouts and add an embedded Spotify link as well, because I want Donald Glover to perform “Feels Like Summer” in the little city’s park in my little story.

But then I realize that song is copyrighted.

Once again, too imaginative.

I can see more and more why Barthelme recommended guarding against that.

Also what is this impulse to have Donald Glover, a black musician, play his song that I don’t own in my story, instead of coming up with another example to substitute for the cringe bongo situation?

I should probably guard against whatever that is, too.

Though I then remember that it was because he’s the only musician I love who also happens to have the same first name as the original author of this little story.

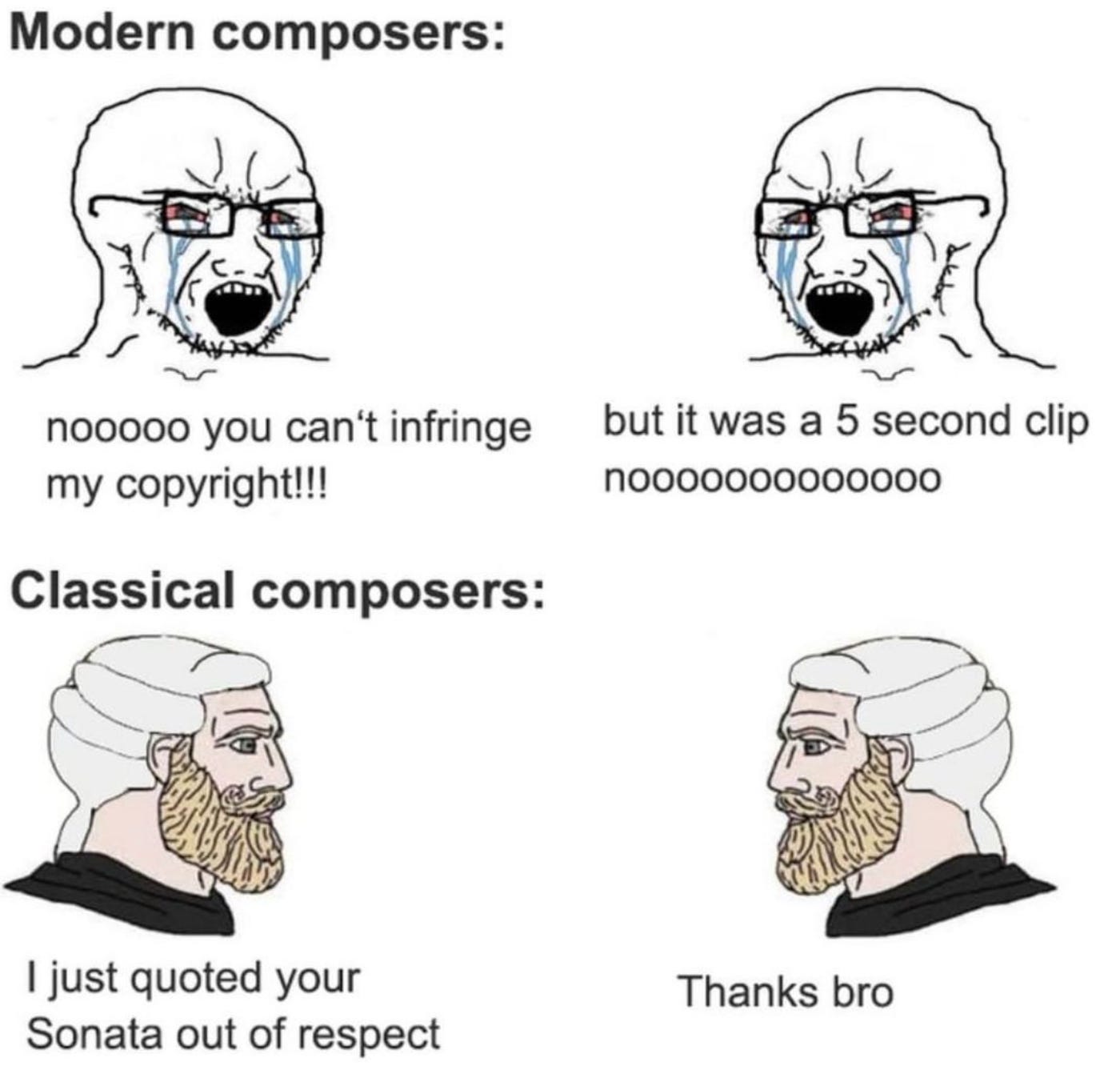

I decide to double-down and add a meme:

I have no idea who owns the copyright to that meme.

Maybe

knows?I then made all the people in the little city dance to Donald (Glover)’s song in the park.

But then I realize I seem to be getting confused in the story, not just between tenses of grammar, but regarding characters and plot, between who is doing what: me, Musk, Bartheleme, his narrator.

So I clarify that I made Musk make all the people in the little city dance to Donald (Glover)’s song in the park.

But that Musk is the one who then made them all tell me they’re enjoying my little story.

And if they didn’t say so Bartheleme’s narrator suggested that they’re banned from both.

Bartheleme told me Musk assured him that he can tell if they say so in an ironic or parodic way and we banned a few of those jokers.

The Childish Gambino sees The Mighty Musk and says, “Nice little city, man,” in a way that’s so hip and cool it’s hard for anyone to tell if it’s sarcastic.

“Thanks,” The Musk Daddy simps. “Got any ideas about what else I can do to make you like living in it?”

“Yeah. Can you give everyone a Universal Basic Income? A UBI? Like they did in Stockton, California for six months? But, like, a lot more?”

“‘Bout how much UBI are you thinking of?”

“Well, not too big.”

“Uh-huh.”

“Just enough to always have food to eat, have a place to live, have clothes to wear, and have medical care if you get sick.”

“So the bare necessities?”

“That would be nice, yeah.”

“You see, the problem is,” The Muskrat started to reply, “Well, I guess, I can’t think of a problem at the moment. I’m currently worth 191.4 billion dollars. And there were 26 residents in the 2000 Census, here in Boca Chica, Texas, which I bought in this remix of the story, instead of Galveston, Texas, and perhaps in real life, too, it’s unclear when you Google it, as well as if I renamed it “Starbase”, both those things are unclear from Googling. Also, I was worth as much as 244.4 billion dollars before, you know, everything went…Regardless, I probably still have more than 7 billion dollars per person per lifetime to give.”

“Nice. Whatever man. Also. Can you get rid of the po-lice? Like not just defund, but abolish it?”

“What about muggists and rapers?”

“I don’t know, man, I’m not a criminologist, but it seems like there will be a lot less crime if people don’t have to worry so much about money anymore.”

That might be right, Musk thought. He had bought the whole city and could probably ensure that.

“Anything else?” The Let’s Be Real Kinda Too Much All For Himself Could’ve Spent 44 Billion Dollars To End World Hunger Musketeer asked. “Do you have anything really imaginative?”

I, the author, once-lowly-but-also-paradoxically-sometimes-too-proud-and-still-sometimes-so, made Glover continue off the path of the story and say “I’ve always thought it’d be fun to have real-life Huxley birds?”

“What are Huxley birds?”

“They’re the parrots in Aldous’ novel Island that remind us over and over to “Be Here Now!”.

“I thought that was Ram Dass?”

“It’s a perennial philosophy.”

“Well,” The Magnificent Musk said, “Let’s give ‘er a try.”

“Thanks. Any song requests?”

“Yeah. Can you play your song ‘California’ but change it to ‘Boca Chica?’ I like to make old things new again but it has to be obvious now, you know?”

“Yeah, man, I know.”

Glover started to sing:

She want to move to Boca Chica

She must've f--ing found her mind

There was a comment. Emma Allen, the editor of The New Yorker’s Daily Shouts, Cartoon and Humor sections Zoomed me after she read this far in the story.

“OK, here’s the thing,” she said, her eyes either gleaming or burning, I couldn’t tell which, it was a poorly lit Zoom, “I like it. Or at least I’m pretty sure I do. But I also feel like I’m just reading a gigantic jiveass pastiche.”

She was right. Read so far, it was like reading an unauthorized, overlong, pretentious, puzzling, onanistic reproduction of Barthelme.

“Everyone knows that…” I reply, “But what my story presuposes is: maybe it also isn’t?”

I almost add, “I guess I can just publish it right now on my Substack?”

But thought it best not to mention that. Or that I already sort’ve did with an earlier draft.

Instead, I offer to consider squaring off the story in the ways Emma may see fit, e.g. this part for sure probably. I do believe editors improve concepts. I tell Emma I run across more than the occasional formal innovations on Daily Shouts that surprise me.

“That’s nice,” she smiles, both of us unsure, perhaps wary, of how she became part of the story.

I consider swapping Emma’s name with Susan Morrison’s, who championed my first and only accepted submission and may or may not still remember me or be the editor of the regular magazine’s Shouts. I notice the word count, and that the original story was categorized under Fiction, and consider swapping in Deborah Treisman’s name. Then debate cutting this all out in my mind, then with my therapist, as well as not submitting the story whatsoever. But then say to myself:

Got a little story

At least it ain’t boring

By now I had exercised my proprietorship so imaginatively and at the same time, if I do say so myself, somewhat tactfully, at least for me, that I wondered if I was enjoying myself too much.

I had only worked a few hours on the first draft in 2021, then a few more hours in April and June 2022, and then for the most amount of hours a few months after that now in November 2022, and now a bit in January 2023.

How long did the great master Barthelme labor on this little story when it was his intellectual property?

Did he impulsively tear through it like Musk seems to like to do with his?

I decided to follow the great master’s structure and have El Ron Mean Mister Mustard Hubbard shoot six thousand of the Huxley birds.

This gave me great satisfaction as I came up with the Island reference earlier in the first draft without planning to substitute birds for dogs, which were the original animal Bartheleme’s narrator shot six thousand of.

And, of course, I had no idea how wonderful it would improve the story for the better when this happened:

Even if Musk was right now perhaps the vilest creature in media, maybe the world at large, and I should be writing a serious op-ed or rage-tweeting a thread for more virality about how long were we all going to sit still while one man, one man, if indeed so vile a critter could be so called, etc. etc…

From another point of view the sequence also suggested I was and am channeling genius, by that I mean whatever you call the thing that’s truly doing the writing: the Muse, a daemon, the Tao, ‘God’, etc. etc…

But, of course, from yet another point of view I’m aware that such spiritual mumbo-jumbo is also at least half of a hedge on a bit of my own late Kanye West-esque unhealthy Enneagram 7 self-ref(v)erential delusions of grandeur narcissism, Musk too?, which can be so off-putting and probably part of the reason I’ve never had another story published in The New Yorker, etc. etc…

It seemed the man whose parrots I’d had shot DMed me.

“You shot my birds,” Aldous Huxley said. Or someone impersonating him. I couldn’t verify yet.

“No, I didn’t,” I replied to the dubiously blue-check-marked citizen of my little story’s city’s social media app, “I had them shot by the narrator of this story.”

“Right, I guess that’s true,” responded maybe: Aldous Huxley.

“Does that mean you don’t want to bust me over the head with a short length of pipe?”

“No,” @you.are.not.in.a.dystopia.you.just.believe.you.are.jpeg DMed back.

“I still do,” A yell was heard behind me.

It was the real Aldous Huxley showing me the short length of the pipe he brought for the purpose.

“But why?” I asked another dead hero inserted into my story without consent, “The birds are fictional both in your story and mine?”

“Because you misquoted my birds, gaucho. They say ‘Here and now, boys,’ and ‘Attention.’ That’s the trouble with you post-post-modern writers, you haven’t even read enough of the works you reference.”

“Mister Huxley,” I said, “There are now more words published every year than in all the years before, ever year. You expect me to know another story of yours besides the one they made us read in school?”

“Barthelme always read what he referenced.”

“You don’t know that?” I exclaimed. “I read Island. And do you know what else I know?!”

Huxley looked like he didn’t care about what I knew but cared about me nevertheless.

“I’m the sole owner of this story” I said, “And, therefore, this sentence, the sentences you just said, and the ones you once wrote, in a book, a magazine, or any platform of mass communication. They’re all mine here. So I can change what you say here and what you had your birds chirp in your little book!”

“You wouldn’t do that.”

“I’ve been known to do worse. Maybe I’ll post a poll that leaves what to do with you out of your and my control. I’m a black-hearted man. So I’d leave it susceptible to interference from bots and bad actors. Because I don’t believe in Hell, so why should I give cooling drafts of mercy to any quarter?”

He went away aware of and sad with my intellectualization of my thwarted ambition.

And I was not any happier either.

I thought for a moment I needed to be struck still with that bad-looking piece of pipe he had had there. But I was over 2,000 words ahead of the game, in a sense.

I couldn’t think of any more post-1974 literary innovations just then except for an attempt at autofiction I tried in an earlier draft about an ex, which would likely get me punctuated like the still-alive [insert your beloved/loathed transgressive/shameless autofiction author’s name here].

And, more importantly, such a thing wasn’t an example of the kind of writer or person I wanted to be anymore.

Just then, I wandered into a store on Tremont Street, a woman whose name I couldn’t verify either, because she was too unpopular or humble or sensible to have requested or paid for my story’s city’s social media app to do so, saw me and called out:

“Hey!” with considered friendliness, “Can I ask you a question?”

“I suppose.”

“I thought you bought this so that ‘Everyone can have their own say here’?” She said. “Do you still believe that?”

“A little bit.”

“Okay. And so. Did you mean to make such big changes overnight?”

“Not with such dismal results, no.”

She poured that kind intelligent look of hers at me and said, “You know, I have one and one-third lovely children. And when I met my first one, my first thought was: I have never seen that much goodness in a person’s face before.”

I still don’t know if we’re supposed to congratulate people who are pregnant but haven’t had their child yet, but I congratulated her anyway.

She said thanks.

Then added: “Do you know what I learned from that?”

I shook my head, No.

“Every parent has that same thought about their child. That they’ve never seen that much goodness in someone’s face before. And that’s also what God thinks. Or the Universe. Not just about every newborn. But of everyone. All of the time. Any time of their life. Do you understand what I’m saying?”

I immediately had this thought:

I don’t really own this story

Awful pity

Can’t help myself

Can hurt myself though

And others

Publish a remix of a copyrighted story

Mess it up

Be too imaginative

Best to leave it alone

But who decides

Donald’s story is The New Yorker’s

And coveting

Is not nice

You’re not entitled to it

Or anything else from them

Same with a partner

Even if they were yours

If they’re not anymore

Must give them back

To the sea of love

Let them be

And you fish for others

Perhaps same with Elon

Give Twitter back

I wrote here last year

To the sea of what Jung calls the opposite of love

Which is not hate or indifference

But power

So the opposite of that

Which might also be the kind of love

That has no opposite

That’d be a nice place to live in

And write a story about

But since then

Musk has promised to step down

And has also changed how he’s running it

And now

I seem to be publishing this story

Regardless of the above

Can I remix the fish and story metaphors again

Into a palatable-OK-to-publish-proving stew?

Maybe I am

A smaller fish

Eating a bigger one

Because its time has passed and it’s dead

So no one really minds

If its remains, its materials

Are put to good use

And

If it is really yucking someone’s yum

LMK!

In the penultimate paragraph, Barthelme’s narrator says “I learned something - Don’t play God.”

I think I learned some sort of a corollary - “Play with others how God plays with us.”

To me, that means something like: Imagine anything and be free, but respect certain restraints and boundaries; the definitions of which are subject to change.

A lot of other people probably already knew that. Maybe not. It’s a bit wonky.

Sometimes I’ve believed for more than a few moments that I’m smarter than other people, but usually I figure out I’m not again not nearly as quick. (I think I wrote that right?)

So what’ll happen next?

I’ll likely take a bath on the remix of this story, there’s no denying it.

Unless, of course, The New Yorker is somehow interested in selling it to me, then re-buying it back, for more money, or something like that.

But yeah, I guess I’ll submit it to them now.

As you can probably guess, it’s quite a long shot.

That’s OK though.

So was the Kanye one.

It was even rejected first before it was then accepted for publication (maybe the same will happen with this one, too, LOL)

There were then 10 years when I thought I was cursed to never be published there again. That was torment.

Then came the things God did to my family: the death of dad, recurrent manic episodes, end of marriage.

Somehow all of that though began a new/old way of living/writing without as much concern for outcomes.

It’s been powerful.

I guess that’s a sample of an Imagination more unknowable than all words.

Not just its pronouns.

And if people still ask me, When will you finally get another story into The New Yorker?

I can say, I don’t know, but let me send you this one, it sure was fun to play with.

It’s on my Substack. Because after it was rejected, I debated whether to publish it. And Shuffled no joke/no lie to this Synchronicity:

You ain't gotta like it 'cause the hood gone love it (hey)

You ain't gotta like it 'cause the hood gone love it (hey)

Watch a young n— show his ass out in public (hey hey)

I got the whole block bumpin' (hey)

You ain't gotta like it 'cause the hood gone love it (hey)

🔀 ✨